- Home

- Stefan Barkow

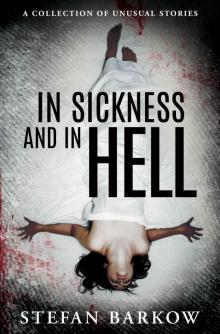

In Sickness and in Hell: A Collection of Unusual Stories Page 9

In Sickness and in Hell: A Collection of Unusual Stories Read online

Page 9

It is not the form that is at fault here, it is we, the artists. We must put aside our old standards and strike out in new directions, as we have in the past. Remember when we first began the technical art of world building? How difficult it seemed, how time consuming? Now, it is merely the first step on a longer list. But emotion-weaving is a finer art, an expressive one, and it must not follow the same narrow path.

The techniques and the guidelines that we have been relying on as we painted these worlds with life must adapt and evolve. The efforts of the past were good for their time and served to teach us much. But be honest with yourselves; after witnessing this, can you deny that the others were of tragically limited design?

It was in reflecting on my last work, Joy, that I conceived of all that I show you here today. The crucial axiom to remember is simple: it is variety alone that gives meaning to consistency. A singer’s ability to hit a high note is impressive, but one note is not a song.

Joy is guiltier than most of violating this rule. That world was hailed for how well it expressed such pure emotion through the life upon it. A few slips of the brush showed, some pain here and there, but that all was deemed unavoidable in a galaxy governed by inflexible rules. While there is nothing wrong with expressing pure emotion in itself, I came to understand that it is both a benchmark and a dead end. If followed further, it will only stagnate the art. There is no variety in a pure emotion, and because of this it lacks for meaning.

And this art is capable of so much more than that.

Once I had conceptualized this, my whole viewpoint changed. The pain of “Joy” was suddenly its most interesting asset because it provided the only variation in the entire piece. I began intentionally incorporating more pain into my new project, thinking to expand on it more fully, but quickly realized that it was not the solution I sought. It helped the feel of the work, but it seemed too amateur a fix for such a fundamental problem; there was no substance to it.

So then the problem became how to create the variety I sought. I pondered over what I could tinker with, the variables that were at play. I created species after species, hoping that one would give me a clue to the answer. At last, I found a variable so few had ever manipulated that its existence was largely forgotten. I realized that neither I nor any of the other artists I know of have ever made creatures that were aware that they were alive and, as a corollary, were not aware that they would die. Such a creation has been avoided, I think, because it is too risky; the artist who tried would be risking his control over the piece, which negates his ability to claim it as his own.

Something told me that my answer lay in that one little variable, so I took that risk. My goal was variance; is it not reasonable to presume that variance would occur from a loss of control? Well, I was curious enough to think so. I left my other creatures to die and began an entirely new set.

My first attempt was to go to the other extreme; I made creatures that had knowledge instead of ignorance. At the time, I thought I would get opposite results. As it turned out, I was right. Too right. The result was what I should have expected. Opposite, yes, but just as stale. These new species, these naiads and golems and the rest, given knowledge of their death, its time, place, and cause, were filled with pure sorrow instead of pure joy. Death-fixation afflicted each and every one; what pleasure could they have when all their time was spent counting the seconds that remained to them?

So yes, they were different, but no less static and no more interesting than their precursors had been. The emotions were reversed but the results were the same. Boring. Static. Invariable, even on an individual scale. It didn’t matter what the emotion was, the problem was that it was set in advance—a single, inescapable result stemming from the setting.

But my efforts were not wasted. I forged on, still strong in my faith that the answer was related to this variable, somehow. It was only after a few more failed attempts that I realized that the efforts at the extremes had inadvertently defined a range, and a range has, of necessity, a median. So I began work within this third option. What I had learned was that the spices of knowledge and ignorance are too strong on their own, that they must be blended if they are to be enjoyed. Perhaps even beyond the sum of their parts.

I began to work again, molding a new species and imbuing it with knowledge and ignorance both: the knowledge of their own death, the ignorance of when, how, and why.

I found that the results were even better than I had expected. My creature knew not just joy and sorrow, but something else as well, something new. Unlike the first set, this being could think about the coming of these things, could dream about joy and could fear the sorrow. Unlike the second set, it was forced to wonder about these things when it looked to the future, because it did not know when or what would happen to it and those that it cared for.

That, my fellows, is the secret to the piece you absorb even now; that unique feel, that flavor, that texture, is the uncertain future. Potentiality. Dynamicity. And most importantly, the byproduct of the two, catalyzed through this little being: worry.

I think it is the most beautiful thing I have ever created. Something new that varies not just as a whole, but from creature to creature.

I have worked in the medium of life for a long, long time, but only now, with Worry complete at last, do I begin to feel satisfied.

No other world I have ever made is worth looking at more than once. Worry is different; I feel as though I could watch this world spin until the stars burn black, and it is time to begin again.

Forgive Me, Father

The Call had been more a feeling than an actual sound. It had glided down a mountain and rolled over hills, through creek and cleft to find him. It had looked in his fields, his barn, even his small shrine at the limit of his lands. The Call had at last found him sleeping in his bed. It had been nearly midnight. He’d had no way of knowing about the forces at work in his world then, or of the terrible events that would befall him in only a few days. He’d had no way of knowing that his quest would end in what many would view as mankind’s ultimate tragedy, or that he alone would be held responsible for it.

The holy presence had not disturbed his wife nor any of his four children. The farmer, skin tanned by years of hard, honest work, had sat up in bed with eyes wide when he felt the summons. Not for a second had he doubted what he had felt. Not for a second had he hesitated with what he had to do. He had dressed quickly in the dark bedroom, putting on a simple tunic and loose, faded pants. He took his best robe as well, but this he carried rolled up so that it would be clean when he reached his destination. His wife had smiled in her sleep when he kissed her. Before leaving the house, he had lit a candle as he recited the prayer of protection for his family, asking the flame to watch them in his stead. He had done the same for his land when he had passed the small shrine he’d erected at the corner of his property.

Lighting the candle there had sparked the proud memory of the day he had built that shrine, ten years ago. He had been twenty-five years old at the time and his new wife was a month passed her twenty-second birthday. The wedding had been beautiful and grand, with guests from the other side of Valley: a full two days journey. Their union had been planned far in advance. At her birth, before his family’s farm and name were destroyed by the fire, her parents and his had signed the contract.

The farmer had walked into the night as he thought about his past, encouraged onwards by the pull of the Call. He had felt no fear though he knew the dangers that lived in the forests lining the main road. That night the beasts had slept, and the full moon alone had watched in silence as the farmer made steady progress beneath the cloudy sky.

The fire. Even though his parents and both his siblings had survived, it had destroyed their family name. His father’s shoulders never seemed quite as square afterward, and although his mother tried to be happy, by his twelfth year the boy had realized it was just an act. When they went on the monthly trip to the town market, he would hear the older men mutterin

g of the cursed family as their wagon passed. Once, after the family returned to their burnt land and small hovel, he had asked his father about it. He’d never seen his father cry before. He never asked about it again.

The farmer had been following the Call for over an hour and his strong legs had carried him far past the boundaries of his property, into the foothills of the Mountain Sacred.

No one but his parents knew why the family had been punished, but everyone knew that their god must have a reason, that some terrible sin must have been committed. Even as his family had struggled to survive without workable land, his promised bride’s family had flourished. The girl had been the most beautiful in all of Valley and the promised bride to the first born of a family publicly disgraced by their god. His eventual marriage was saved by two things. The first was that her family was old and honorable and would not dare commit the greatest sin their society knew: the breaking of a signed contract. The second reason was that as soon as he was old enough to comprehend the reason his family name was spoken only in whispers behind his back, he had striven to become the most devout man anyone had ever seen in Valley. Whatever his parent’s sin had been, none doubted the boy’s ability to atone for it.

He had listened to the sounds of his sandals slapping against his feet as he followed the summons faithfully. The air had felt warm, with the promise of intense heat come morning. The farmer had covered many miles as another hour had passed and still the Call did not relent but instead urged him forward. He hadn’t felt tired or weary. He had kept his mind active with memories from his past, softening the hard path he walked now with images from the paths he had traveled before.

After the marriage celebration, his bride had taken him to his new land. It was enough to put honor back into his family name, if he put in the work. The unbroken fields were not close to town, but the soil was good and it was a generous gift. They had gone on to build their house and farm and family. Their first construction had been the small shrine along the wide old road that bordered the edge of his new family hold. He’d selected each stone with care, and he had asked her to paint the simulacrum within. She had worked meticulously, knowing how much it meant to him. Every single day the farmer had cleaned and stocked the shrine with candles for anyone who sought to pray. When their first born boy had turned seven, the farmer had passed the sacred chore on. Like his father, the boy never missed a day. Travelers and merchants who passed called it the Shrine of the Narrow Path. The name came not from the road they themselves traversed, but because of the road the farmer who had built the shrine followed. Many stopped to say a prayer and all bowed their heads as they passed; some in respect of the god and some in respect of the man.

The third hour had passed him somewhere along the road, and the farmer had reached the base of Mountain Sacred at last. The Call had summoned him into the woods when the road turned aside to begin its lengthy climb to the summit. He’d walked through the forests, and had gone on as the ground sloped upwards beneath his creaking sandals. He had followed as the dirt turned to rock and the forest had thinned and ultimately disappeared except for a few bushes that held desperately to the rocky soil.

It was from this timberline that he had first caught sight of the eternal fires that held the inky night away from the Great Temple. It was said that in all of Valley, no location brought man closer to his creator than at the summit of Mountain Sacred.

A short time later he was led into a river. The water was pure and cold but only as deep as his neck. He had crossed with his bundle held high above the water, and he had not allowed a single drop to touch it even as the currents had worked to confound his journey and sweep him down into the lake at the floor of Valley.

He had made the far bank as the first fingers of the sun had shone on the horizon and had begun their day’s labor of pushing the sun to its zenith. A seemingly futile endeavor, since the evening would see the sun roll beneath the horizon again, yet one which brought light and life to the world.

The farmer had wanted to stop and rest on the wet, rocky bank but the Call had become more insistent, telling him he must go on. From where he’d stood, the only way to go on was to go up. So up he had gone, slinging his bundle across his back and removing his sandals before beginning the ascension. The face of the cliff was not quite vertical, but very nearly so. Had it been vertical he would probably not have made it to the top, although he would have tried. As it was the winds of the morning—fed by cold air at Valley bottom warming and rising under the sun—almost tore him from the mountain face. He was forced over and over again to sink his fingers as far as he could into the crags, imitating the plants he had left far behind him, waiting for the gusts to subside.

Unknown to the farmer, it was during one of these times that his wife had awakened. She had been dreaming of their childhood, growing up separately but knowing that one day they would be together. He was not a hard man to love, really. He was honest in everything he did and while that in itself infuriated her at times, their love truly was that simple. Sure they had fought, but they’d always forgiven each other afterward. After all, they were only human.

When she realized he was not in bed, she had searched the house. When it became clear he’d gone, she became afraid. Without knowing exactly why she did it, she woke their two sons and two daughters, dressed them, and led them to the shrine. She had once asked why he didn’t build another shrine closer to the house. He had told her simply that when worship became too convenient, it ceased to be worship. The way he had said it was as a man thinking aloud, as if he always knew he had a reason but never knew what it was until she had prompted him to tell her. They’d only been married about half a year then and, though they had felt as if they loved each other before, this moment was a milestone in their marriage. They both realized the depth of their partnership, how they could give value to each other beyond themselves. The question was just as important as the answer, and each revelation was not his or hers but theirs.

When her children had completed their prayers at the shrine, they had gone back to the house to begin their daily chores. She was the last to leave the shrine.

Even as the last amen passed between the lips of his youngest daughter, the farmer was achieving the summit. He rolled onto his back, his bleeding fingers shaking from the exertion. It was well into morning now, and in the light of day he saw his own appearance. The Call had left him when his fingers had stretched over the lip of the abyss at last. He needed no more guidance now, for it was clear that the temple was his destination. His simple clothing was streaked in mud and shredded from the rocks. He cleaned his hands on the tattered shirt and opened the roll he had protected all night. Inside was his best clothing: a long robe dyed dark blue, the color of the night sky just before the eyes of the stars have opened. He changed into the robe and bound the waist with a silver chain his wife had bought for him on an anniversary. Like the robe, the chain was not particularly ornate but the material was pure and the design simple. To him that made it sacred.

The road ran between him and the front of the Great Temple, looping around and rejoining itself on the far side of the structure. Across the road he saw the eternal fires raging in the bowls of beaten iron. There were seven of them. Three stood along each of the side walls, like pillars of flame supporting the sky. The seventh stood directly in front of the middle of the door. Each bowl was held eight feet in the air by worked iron stands and immediately behind these vigilant guardians stood the Great Temple itself. The farmer had visited before, though not often. The path he had taken this time was unheard of. All pilgrims took the one road that led up the mountain, but it had been built before the temple. The builders had needed a road their wagons could climb to bring up cut stone and other materials from below. Because of this, the road twisted back and forth to cut the angle of ascent. Long detours had been shaped to avoid pinches and impassable terrain as well. Had he taken the road from his land, it would have taken him much closer to a day and a half to arrive.

<

br /> The farmer stood in awe of man’s accomplishment. The grey stone of the outer walls had been smoothed and polished so that they looked almost to be made of glass. Proud columns braced the overhanging edges of the steepled roof. Closing his eyes, he muttered a prayer of thankfulness for his safe arrival. He’d come up the east face of the mountain and the entrance of the temple looked north so he followed the road around the corner to the front. The iron-bound timbers of the door were opened outward and he had to pass very close to the seventh fire bowl to go inside. Even in the wind, he began to sweat from the intense radiant heat.

The eternal fires were a miracle in themselves. They’d been designed to hold fuel, and some said that originally a rotation of priests had intended to arrive every other day to refuel them. But the first service had been held before the fires had been lit, and when the opening ceremony ended, all seven fires had sprung up as one and had needed no fuel since that day, in the times of his father’s father’s father.

The interior of the temple was simply beautiful. Its design did not attempt to overpower the pilgrim by overloading them with frivolous detail when absolute majesty worked better. This was a house of worship. The interior walls were plain and polished like the outer walls, but the ceiling was a masterpiece of wood carving. In great panels, the planets and the moon hung in their spheres around the earth. He couldn’t help thinking that the stars of the outer sphere were shining, even though he knew it was clever carving and polishing to reflect the light from outside.

The temple was one large room, with strong wooden pews taking most of the space. The farmer walked purposefully to the front of the temple and knelt before the great statue of his lord and creator. According to legend, a lone artist had cut the stone to bear the face of the god and when he had finished, after gazing at the beauty of his creation, he had walked out of the temple and leapt from the cliff, knowing he could never do anything as great as this for as long as he lived. The kneeling man knew this story and had told it to his children many times, though he doubted that there was any truth to it.

In Sickness and in Hell: A Collection of Unusual Stories

In Sickness and in Hell: A Collection of Unusual Stories